Unbounded Space – Infinite Black

Observations on the Landscapes of Philipp Haager

by Alexander Eiling

“Landscape is for me the key to contemplating existence!”

Philipp Haager’s statement on the occasion of an exhibition of his work at the Karlskaserne in Ludwigsburg in 2003 forcefully attests to the artist’s interest in a genre that seemed for a long time to have no place anymore at German art academies.

Haager, born in Bad Canstatt in 1974 and a graduate of Christa Näher’s class at Frankfurt’s Städelschule, embarked a good ten years ago on an exploration of landscape in a wide variety of art forms. Paintings, drawings, prints, but also conceptual works made of Lego bricks or towels demonstrate his ongoing efforts to find new ways to approach this subject.

Back when he began his studies in 1999, Haager produced a series of sixteen works on paper that, in retrospect, would in many ways lay the groundwork for and decisively influence the course of his painting in recent years. Sequenz (Sequence, figs. 1 and 2) is the title chosen by the artist for this experimental series of images in which colour is used autonomously, largely detached from representational demands, as a means of expressing instead atmospheric forces, light, darkness or meteorological phenomena. Associations with landscape are reduced to the extreme here, and yet the motifs still appear to be drawn from observations of nature. For Haager, every sheet in the sequence can stand on its own, but he nevertheless presents them as a composite large-scale image in which each individual depiction contributes to the overall effect of a sum of landscape impressions.

The fact that each individual work can be only part of a holistic and ultimately unfathomable experience of nature, the representation of which pushes the artist to his limits, may have been the reason for a break of several years in Haager’s painting, during which time he devoted himself to conceptual projects.

It was not until the 2002 painting Ohne Himmel (Without Sky, fig. 3) that he again tackled a large-scale landscape panorama, one that would greatly exceed the dimensions of his previous works. The image shows a view of a broad range of hills crisscrossed by jagged rifts, stretching into the distance without detailed topographical reference points. Shades of green, brown and blue are applied in flowing washes of oil paint, creating a transparency that is astonishing for the medium, more akin to watercolour.

Despite its outsized format, the painting gives the impression of being a sketch. The canvas in the sky zone is left entirely bare, contrasting with the painted areas in a daring balance.

Philipp Haager would deliberately employ this aesthetic of the unfinished, so central to an understanding of art ever since modernism and even before, as a means of expression in the works that followed. Exploiting the tension between painted and unpainted surfaces, he proceeded to produce works with varied and more concisely expressed motifs (fig. 4). While at first we still think we can recognise nameable things in these pictures, the pure structure and tonality of the colour and its layering increasingly come to the fore. Each detail appears discernible only to the extent that it serves the overall impression. The coherence of the landscape is more important to Haager than the individual object.

The works of these years share a fragile, excerpt-like character that is closer to the artist’s preparatory studies than to large-scale paintings. This apparent contradiction, with the sketch transferred to the representative format of history painting, often in the form of a diptych, is one of the special qualities of Haager’s art in the years between 2002 and 2004.

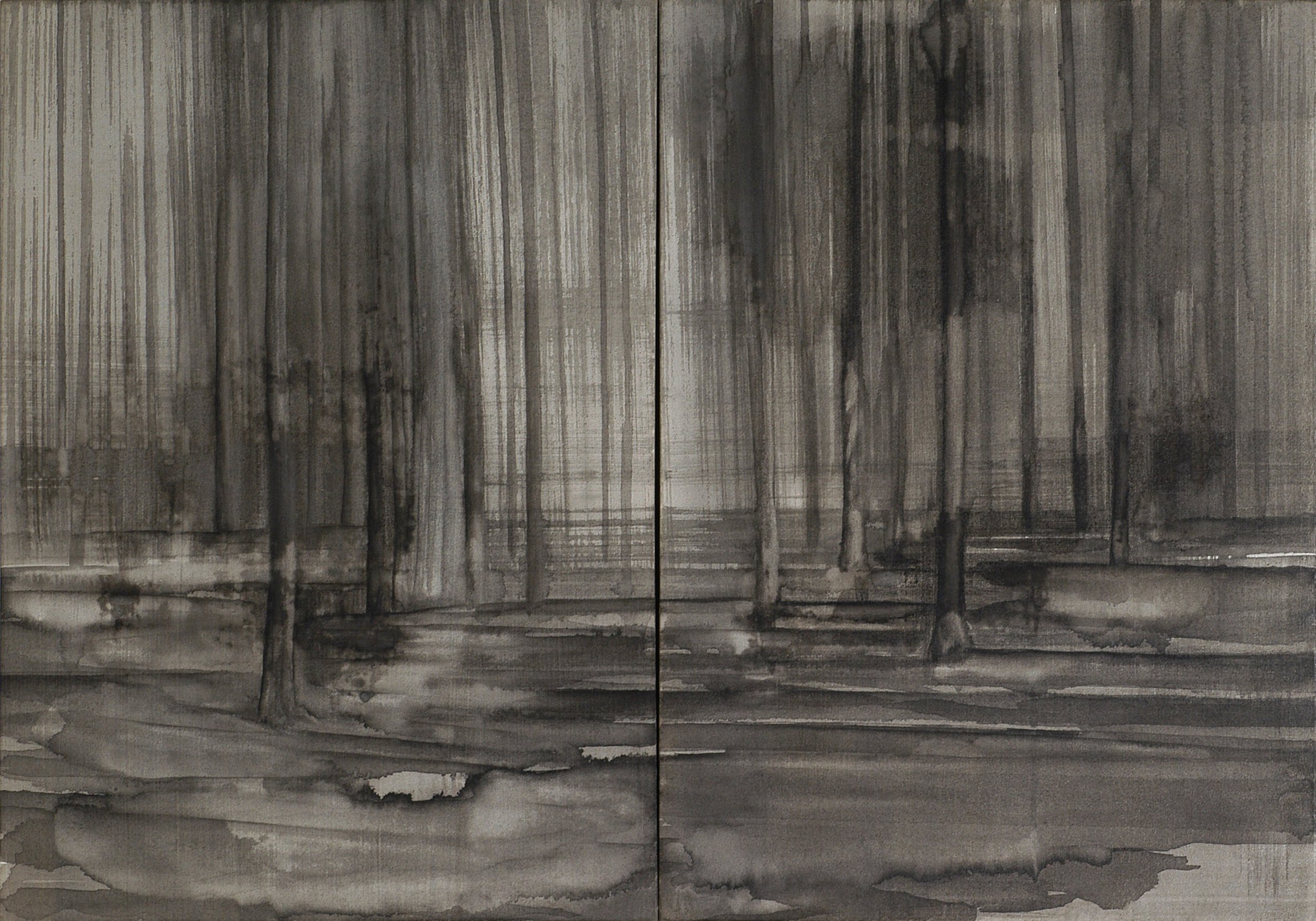

As a counterpart to his horizontal landscapes, he concurrently produced a series of forest paintings, which, under the titles fast alles senkrecht (almost everything vertical), Waldpredigt (Forest Sermon) and Walddiptychon (Forest Diptych, fig. 5), show a vertical row of tree trunks whose crowns the artist has omitted.

Our gaze into the distance is obstructed, redirected into the depths of a gloomy forest, summoning memories of Baudelaire’s conception of nature as “a temple with living columns”. The artist breaks up the austerity and static nature of the motif with a delicate glaze-like application of paint similar to that in his landscape panoramas, a mode of depiction that betrays nothing of the texture or materiality of the trees. The forest appears to be lost in the mist, strangely blurred, a timeless dream image conjured by the artistic imagination.

Haager’s forests are free of the historicity that we would tend to impute given the tradition of forest depictions by German artists, thinking here especially of Anselm Kiefer. They are not the scene of historical tragedies, nor are they patriotic symbols, but rather examples of a kind of painting that takes a particular interest in the abstract qualities of the motif.

Haager’s forest scenes heralded a development in his work that can be circumscribed by the concept of darkening and obfuscation. Decisive here is the use of black ink, which after 2004 would become the artist’s definitive working material. For the 2005 portfolio von Grauem und Güldenen (On the Grey and the Golden), he drafted a sequence of landscapes on 24 small sheets of paper that, in addition to the already familiar hills, evoke associations with waves, sea spray and surf.

These works illustrate how Haager’s various artistic strategies coexisted at this point on equal footing: whereas in some images he abstracts a found or imagined motif by reducing the rendering or rubbing off layers of paint already applied (fig. 6), in other cases landscapes are created solely through random patches of paint and colour gradients (fig. 7).

That the evocative power of indeterminate forms appeals to the viewer’s imagination much more strongly than the descriptive passages of a painting seems to be a realisation that the artist drew in part from his early works on paper. Landscape elements are from that point on merged into an atmospheric colour space in which traditional composition by way of horizontal or vertical layering is largely eliminated (fig. 8). The pale tonality made up of ochre, green and blue tones of the early pictures has at the same time given way to a concentration on black and grey – the fragmentary landscape sketch from 2002, for example, displays a dense all-over structure that leads our visualisation of space astray.

Applied wet-on-wet to the unprimed canvas, colour glazes of varying density conspire here to create a rich palette of greys and blacks that instantly casts doubt on any suspicion that this might be a case of monochrome painting. The density and materiality of the colour are in fact highly differentiated through the pouring, smudging and rubbing off of the ink. This is a time-consuming process that requires the complete drying of each layer before a new one can be applied.

Much more than a purely aesthetic preference, the concentration on black ink is for Philipp Haager above all part of an artistic clarification process aimed at condensing the motifs and formal language of his painting. As early as 2003, after his first forest pictures, the artist was already emphasising how dark painting offered him an opportunity for further development: “Sometimes you have to paint a dark picture to break free!”

But it is also the ability of black to generate space and depth, its existential and metaphysical qualities, that contributed significantly to heightening the effect of his images.

All the while, Haager continued to work consistently on the borderline between recognisability and an ambiguity that stimulates the imagination. In their shadowy suggestiveness, his pictorial spaces seem to be based not so much on what the artist has observed as on dream-like associations. The impression of nature has receded into the background here as the painterly medium asserts its independence. The titles, some of which the artist found to be onomatopoeic, such as Triadras, Vengur or Prigaion, are intended to further fire the viewer’s imagination but without prescribing a specific direction in terms of content.

In Haager’s conception of landscape as a pictorial formula reflecting an inner attitude, and in his endeavour to adapt an objective concept of nature to subjective perception by means of extensive abstraction, we can ascertain certain features of Romantic painting. This is a classification the artist had however long rejected due to what is meanwhile an inflationary use of the term in contemporary art.

As early as the mid-1970s, Robert Rosenblum, in his study of modern painting and Romanticism, raised the question of a spiritual affinity between the two eras. [1]

Haager’s painting is seductive in this respect, as visions of works by artists such as C.D. Friedrich or William Turner invariably come to mind when looking at it. Panoramic expansion of the field of vision, cropping, infinite and incomprehensible spaces, a sketchy style, an evocative quality inherent to painting – all these characteristics have after all been attractive points of orientation for many modern artists, including Haager, without necessarily positing a direct dependence on what went before.

A close examination of Philipp Haager’s works shows that he has achieved an astonishing course of development in his art over the last few years that can only arise from long years of engagement with a motif. We can trace this process from the initial observation of nature to its gradual abstraction and onward to the purely imagined landscape that is more a felt than a real space. The artist’s own inimical way of viewing his surroundings, his freedom in handling his painterly means, and the consistency of his work have thus far resulted in a promising oeuvre, the further development of which will be exciting to follow.

[1] Robert Rosenblum, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko (New York, 1975).

Fig. 1:

Sequence 5 (from a 16-part picture sequence, 280 x 400 cm)

1999, 70 x 100 cm, oil, pigment & ink on cardboard

Fig. 2:

Sequence 10 (from a 16-part picture sequence, 280 x 400 cm)

1999, 70 x 100 cm, oil, pigment & ink on cardboard

Fig. 3:

Without Sky, 2002, 300 x 400 cm, oil, pigment & dispersion paint on unprimed canvas

Fig. 4:

Diptych (landscape, 2-part), 2003, 200 x 300 cm, oil, pigment & dispersion paint on canvas

Fig. 5:

Forest Diptych, 2004, 70 x 100 cm, Indian ink on nettle

Fig. 6:

From the series “On the Grey and the Golden”, 2005, 20 x 30 cm, Indian ink and gold pigment on handmade paper

Fig. 7:

From the series “On the Grey and the Golden”, 2005, 20 x 30 cm, Indian ink on handmade paper

Fig. 8:

Philipp Haager, Ingrahl, 2007, 180 x 210 cm, Indian ink on unprimed canvas